Thanksgiving asks us to count our blessings. To gather around tables overflowing with food, surrounded by family, and express gratitude for all we have.

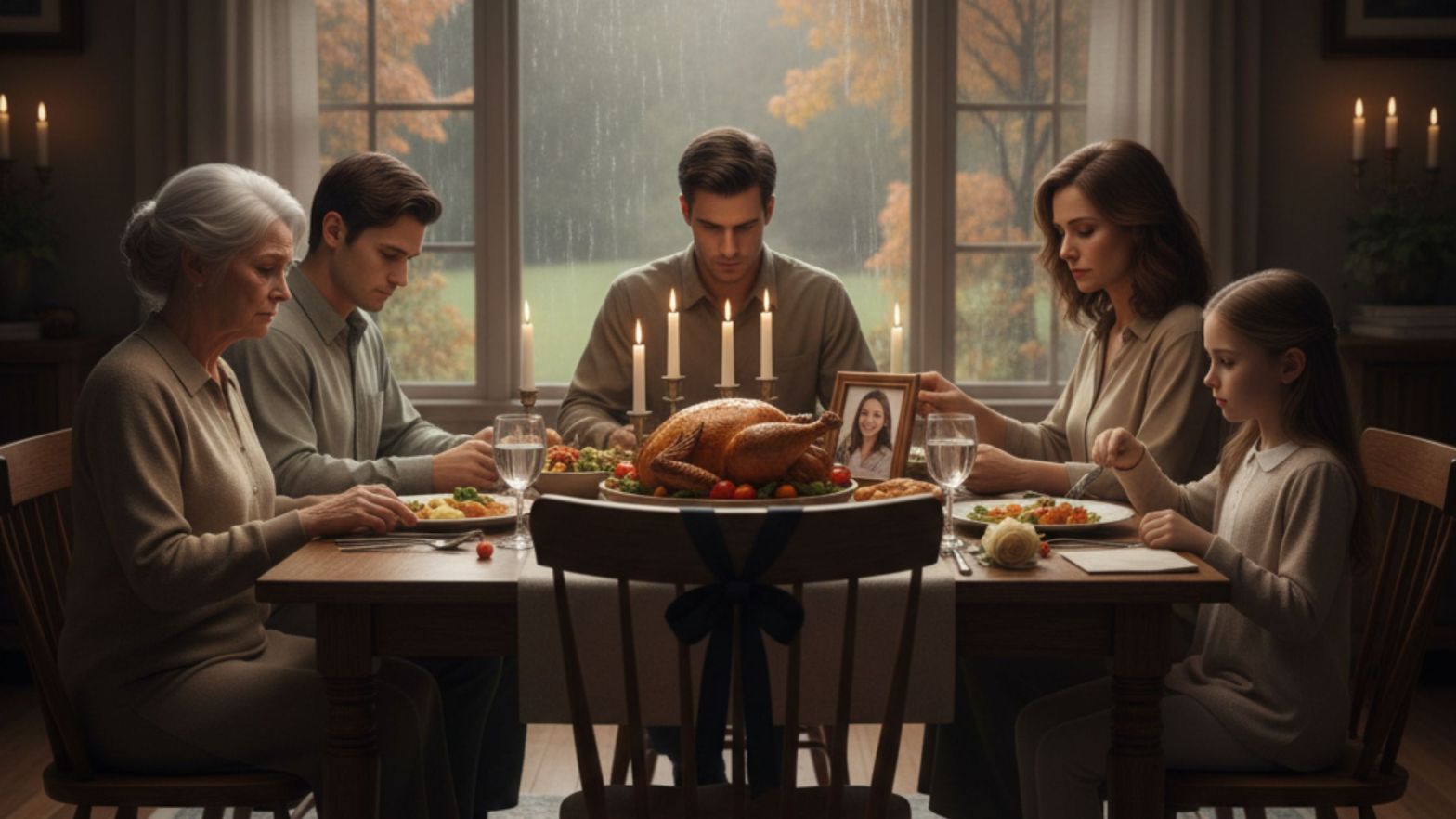

But what do you do when the table has an empty chair?

What do you do when the person you’re most grateful for is the person you’ve lost?

What do you do when grief sits beside you at the feast, uninvited but impossible to ignore?

The cultural script for Thanksgiving doesn’t leave much room for complicated emotions. We’re supposed to be happy. Grateful. Celebratory. But real life is messier than greeting cards suggest. And for many people, Thanksgiving isn’t just about gratitude—it’s about navigating the painful intersection of loss and love, grief and thankfulness, absence and memory.

So let’s talk about the Thanksgiving no one posts on Instagram: the one where gratitude and grief sit at the same table.

The Paradox of Gratitude and Loss

Here’s something most people don’t understand about grief: it doesn’t erase gratitude. In fact, grief often deepens it.

You don’t grieve people who didn’t matter. You don’t feel the ache of absence for relationships that were shallow or insignificant. Grief is the price we pay for love. And in a strange, painful way, the depth of our grief measures the depth of our gratitude.

Think about it:

If you didn’t love them, you wouldn’t miss them.

If they hadn’t shaped you, you wouldn’t feel the absence so acutely.

If their presence hadn’t been a gift, their loss wouldn’t leave such a void.

So when Thanksgiving comes around and everyone’s listing what they’re thankful for, maybe the most honest answer is: “I’m grateful for someone who’s no longer here. And I’m devastated they’re gone. And somehow both things are true at once.”

This is the paradox at the heart of human experience. Love makes us vulnerable. Connection creates the possibility of loss. And gratitude for what we had doesn’t diminish the pain of what we’ve lost—it intensifies it.

Michael Battersby’s Thanksgiving: When Grief Drives the Search for Meaning

In Joseph’s Letter, protagonist Michael Battersby understands this paradox intimately.

His wife Margaret died in a mysterious car accident, leaving him shattered. But here’s what makes Michael’s grief so relatable: he doesn’t just mourn her absence. He’s grateful for every moment they had—and that gratitude makes the loss unbearable.

Michael’s entire quest—his dangerous search for Joseph’s Letter, a document that might prove the resurrection and thus life after death—is driven by this painful intersection of love and loss.

He’s not searching because his faith is weak. He’s searching because his love was strong. Because Margaret mattered so much that he can’t accept that death is the end. Because gratitude for what they had demands hope that they’ll meet again.

His journey asks the question many of us wrestle with: If love is the greatest gift, and death takes it away, what does that mean about the nature of existence?

For Michael, the only acceptable answer is that love must transcend death. That consciousness must survive. That the people we’re most grateful for can’t simply cease to exist.

So he searches. Not to prove God wrong, but to prove love right.

Why Thanksgiving is Hardest After Loss

For anyone who’s lost someone significant, holidays become complicated.

Thanksgiving in particular carries a weight that other holidays don’t. It’s explicitly about gratitude, family, and togetherness. When someone’s missing, their absence echoes through every tradition, every empty chair, every meal that doesn’t taste quite right because the person who always made it isn’t there.

The Pressure to Perform Happiness

There’s social pressure to be grateful, to focus on the positive, to not “bring down” the celebration. So people who are grieving often feel obligated to hide their pain, smile through the meal, and save their tears for later.

But suppressing grief doesn’t make it disappear. It just makes you feel isolated, like you’re the only one at the table carrying something heavy while everyone else seems light.

The Trigger of Traditions

Every Thanksgiving tradition becomes a reminder. The recipe they always made. The seat they always sat in. The joke they always told. The prayer they always led.

Traditions are supposed to provide comfort and continuity. But when someone’s missing, traditions become painful reminders of who’s not there.

The Well-Meaning but Unhelpful Comments

“At least you have other family.”

“They wouldn’t want you to be sad.”

“You need to move on.”

“Everything happens for a reason.”

People mean well. They’re trying to help. But platitudes don’t ease grief—they minimize it. And when someone’s trying to navigate loss during a holiday that demands gratitude, these comments can feel like pressure to pretend everything’s okay when it’s not.

The Myth of “Moving On”

Here’s something our culture gets wrong about grief: we treat it like a problem to solve, a phase to complete, a condition to cure.

We talk about “stages of grief” as if they’re linear steps you climb and then you’re done. We ask people if they’ve “moved on” as if love for the deceased has an expiration date. We expect grief to have a timeline, after which we’re supposed to be “over it.”

But that’s not how grief works.

Grief doesn’t end. It changes.

The acute, overwhelming pain of early loss eventually softens into something more manageable. But the absence remains. The love remains. And on certain days—birthdays, anniversaries, holidays like Thanksgiving—the grief resurfaces with surprising intensity.

This isn’t failure. This isn’t being “stuck.” This is simply what it means to love someone who’s no longer here.

Michael Battersby, months after Margaret’s death, is still consumed by grief. He hasn’t “moved on.” And that’s not a character flaw—it’s a testament to their love.

The question isn’t whether grief ends. It’s whether we can learn to carry it alongside everything else—including gratitude.

Radical Gratitude: Being Thankful for What Hurts

So how do you practice gratitude when the person you’re most grateful for is gone?

By embracing what seems like a contradiction: being grateful for what you had, even though losing it breaks your heart.

This is radical gratitude. Not the shallow “everything happens for a reason” kind, but the deep, painful, beautiful acknowledgment that some things are worth grieving precisely because they were worth having.

Consider these reframings:

Instead of: “I’m devastated they’re gone.”

Try: “I’m grateful I had someone worth missing this much.”

Instead of: “The holidays are ruined without them.”

Try: “The holidays matter because they mattered. Their absence honors their presence.”

Instead of: “I wish I’d never experienced this pain.”

Try: “I’m grateful for the love that made this pain possible.”

This isn’t toxic positivity. It’s not pretending loss doesn’t hurt. It’s acknowledging that grief and gratitude aren’t opposites—they’re companions.

You can be devastated and thankful simultaneously. You can honor someone’s absence while celebrating their impact. You can cry over what you’ve lost while feeling profound gratitude for what you had.

Both can be true.

What Loss Teaches Us About What Matters

There’s a brutal truth about loss: it clarifies priorities with ruthless efficiency.

When someone dies, you suddenly realize how much time you wasted on things that don’t matter. The arguments that seemed important. The grudges you held. The busy work that kept you from being present.

Loss strips away pretense and forces you to confront what’s actually important:

Relationships matter more than achievements.

Presence matters more than productivity.

Love matters more than being right.

Connection matters more than success.

Michael Battersby’s search in Joseph’s Letter is ultimately about this clarity. He’s not pursuing academic glory or proving a point. He’s pursuing the only thing that matters to him now: the possibility of reunion with the person he loves.

Everything else—his career, his reputation, his safety—becomes secondary. Because loss taught him what grief teaches all of us: people are what matter. Everything else is noise.

Thanksgiving Traditions for Those Carrying Grief

If you’re facing Thanksgiving while grieving, here are some ways to honor both your loss and your gratitude:

Create Space for Honest Emotion

Don’t pretend to be fine. Tell people you’re struggling. Give yourself permission to feel sad at a celebration. Grief doesn’t take holidays off, and you shouldn’t have to either.

Honor Their Memory Intentionally

Light a candle. Share a story. Toast them before the meal. Make their favorite dish. Acknowledge the absence explicitly rather than pretending it doesn’t exist.

Rewrite Traditions if Necessary

If old traditions are too painful, create new ones. Move the meal to a different location. Invite different people. Change the menu. You’re allowed to adjust traditions to make them bearable.

Practice Radical Honesty

When someone asks what you’re grateful for, tell the truth: “I’m grateful I had them. And I’m heartbroken they’re gone. And I don’t know how to reconcile those feelings.”

Vulnerability invites connection. And connection is what healing requires.

Let Others Carry Some of the Weight

You don’t have to host. You don’t have to cook. You don’t have to perform strength. Let people help. Let them carry some of the burden. That’s what community is for.

The Question Thanksgiving Forces Us to Ask

At its core, Thanksgiving forces us to confront a fundamental question: What are we actually grateful for?

Is it the stuff we have? The accomplishments we’ve achieved? The comfort we enjoy?

Or is it something deeper—the people who shaped us, the love we’ve experienced, the connections that give life meaning?

Loss clarifies the answer. When someone dies, you don’t think, “I wish I’d worked more hours” or “I should have bought a bigger house.”

You think, “I wish I’d told them I loved them more often. I wish I’d been more present. I wish I’d paid attention to the moments that mattered.”

Margaret Battersby’s death in Joseph’s Letter forces Michael to reckon with exactly this. He realizes, too late, that he took her for granted. That he was too busy with work, too distracted by ambition, too focused on the future to appreciate the present.

And now she’s gone. And all the success in the world means nothing compared to the loss of her presence.

So his search for Joseph’s Letter is really a search for redemption—a way to honor what he failed to appreciate while he had it.

Can Gratitude Coexist with Anger?

Here’s another complication grief brings: sometimes you’re not just sad. Sometimes you’re angry.

Angry at God for allowing it to happen.

Angry at doctors for not saving them.

Angry at the person who died for leaving you.

Angry at yourself for not doing more.

Angry at the world for continuing as if nothing’s changed.

And Thanksgiving, with its emphasis on gratitude, can feel like pressure to suppress that anger. Like you’re supposed to be thankful, not furious. Like anger disqualifies you from the celebration.

But here’s the truth: anger is part of grief. And grief is part of love.

Being angry doesn’t mean you’re not grateful. It means you’re human.

Michael Battersby is angry throughout Joseph’s Letter. Angry at the Church for obstructing his search. Angry at God for taking Margaret. Angry at himself for not appreciating what he had.

But that anger doesn’t diminish his gratitude for the life they shared. It intensifies it.

Because if she hadn’t mattered, he wouldn’t be angry. If their love hadn’t been real, her loss wouldn’t enrage him.

So if you’re angry this Thanksgiving—at loss, at injustice, at the unfairness of mortality—that’s okay. Anger and gratitude can coexist. They’re both expressions of how deeply you’ve loved.

Reflection Questions: What Are You Really Grateful For?

As you navigate Thanksgiving, whether you’re grieving or not, consider these questions:

💭 What loss taught you something you couldn’t have learned any other way?

💭 Who are you grateful for, even though they’re no longer here? What did they teach you?

💭 If gratitude doesn’t erase grief, what does it mean to be thankful for something you’ve lost?

💭 What would change if you prioritized relationships over everything else?

💭 If you could go back and change how you spent time with someone you’ve lost, what would you do differently?

The Gift of Grief: What Loss Gives Us

As painful as it is, grief is also a gift.

It’s proof that we loved. Proof that someone mattered. Proof that connection is possible in a world that often feels isolating.

Grief means you didn’t waste your life on shallow relationships or superficial connections. It means you invested deeply, loved fully, and allowed yourself to be vulnerable.

And that vulnerability—that willingness to love knowing loss is inevitable—is the most courageous thing a human can do.

Michael Battersby’s grief in Joseph’s Letter drives the entire narrative. But it also gives his life meaning. His search isn’t about academic achievement—it’s about love. And love, even when it ends in loss, is never wasted.

A Different Kind of Thanksgiving Prayer

If traditional Thanksgiving prayers feel hollow this year, try this instead:

“I’m grateful for the people who shaped me—including the ones who aren’t here.

I’m grateful for the love I’ve experienced, even though it ended.

I’m grateful for the grief that proves love was real.

I’m grateful for the memories that hurt, because they remind me of what mattered.

I’m grateful for the empty chair, because someone worthy once filled it.

I’m grateful for the pain, because it means I’m still capable of feeling deeply.

And I’m grateful for this moment—imperfect, painful, but real.”

Moving Forward: Carrying Both Gratitude and Grief

The truth is, you don’t choose between gratitude and grief. You carry both.

Some days gratitude weighs more. Other days grief does. On holidays like Thanksgiving, both press heavily.

But that weight is bearable—not because grief gets lighter, but because gratitude gives it meaning.

Michael Battersby carries Margaret with him throughout Joseph’s Letter. Her memory drives him. Her love sustains him. Her loss defines him. And in carrying her—both the grief of her absence and the gratitude for her presence—he finds purpose.

Maybe that’s the lesson for all of us this Thanksgiving: we honor the people we’ve lost not by forgetting them or “moving on,” but by carrying them forward. By letting their absence remind us what matters. By allowing grief to deepen our gratitude.

Because the people worth grieving are the people worth being grateful for.

And that gratitude—painful, beautiful, enduring—is what gives life meaning.

Explore Grief, Love, and the Search for Meaning in Joseph’s Letter

If this reflection on grief and gratitude resonated with you, Joseph’s Letter offers an even deeper exploration of love, loss, and what survives death.

Follow Michael Battersby as he searches for proof of life after death—not because he’s lost his faith, but because grief demands answers and love refuses to accept that death is the final word.

It’s a story that asks: What if love is strong enough to transcend death? And what if the search for that answer is the most faithful thing we can do?

Download the first chapter free and step into a narrative that honors both the pain of loss and the power of love.

👉 Get Your Free Chapter Here

Join the Movement for Transparency

We don’t claim to have all the answers—but we’re asking the questions institutions don’t want asked.

If this post challenged you:

✅ Subscribe to our newsletter for bi-weekly explorations of faith, power, and institutional accountability

✅ Share this post with others questioning religious authority

✅ Leave a comment sharing your experience with institutional secrecy

✅ Support transparency by demanding it from the institutions you’re part of

Because the conversation about power and truth doesn’t end here. It’s just beginning.

And change happens when enough people refuse to accept secrecy as normal.

About the Author:

Robert Parsons is the author of Joseph’s Letter, a novel exploring institutional power, personal faith, and the search for truth. After decades teaching in religious schools, Robert understands the tension between loving your faith and questioning your institutions. His mission is simple: encourage people to think outside the box about religion, challenge authority when necessary, and demand transparency from institutions claiming moral leadership.